Snøhetta celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. In the first part of an exclusive interview with Dezeen, co-founder Kjetil Trædal Thorsen explains that the firm's ultimate aim has always been to make buildings for the betterment of society.

Thorsen and partner Craig Dykers founded Snøhetta in 1989, after winning the competition for the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria, Egypt. At the time, neither of them had ever completed a building.

Projects that followed included the Oslo Opera House, which famously has a plaza on its roof, and the National September 11 Memorial Museum in New York. Both are designed with the idea of creating valuable public space.

"We started off, I think, very clearly with a picture of how architecture could contribute to better social awareness," explained Thorsen.

"We were trying to create buildings that could generate some sort of public ownership – like libraries and concert houses – by changing the attitude towards them."

"We're neglecting our public space"

Norway-based Thorsen had previously been part of a collective of architects and landscape architects. They borrowed the name Snøhetta from the highest peak in Norway's Dovre region, because their first office was located in the attic above a pub called the Hall of Dovre.

When he teamed up with US-based Dykers, they carried on both the name and the landscape-oriented approach.

"In a way, [the library] was something that opened up the possibility of combining this landscape and architectural practice," said Thorsen. "It was maybe the first understanding of how an architectural concept could be contextualised."

"It came very naturally to us," he added. "We were seeing at the time that construction projects didn't have budgets for their outdoor areas. So it was like whatever was left over from the construction could be spent on the landscape."

"We said that this can't be the case, because we're neglecting our public space," he continued. "This is how we ended up at the Oslo Opera House, where there is no differentiation between public space, building and site."

"Architecture is a great societal tool"

As well as creating buildings that integrate public space, Snøhetta also wants to use architecture to make culture accessible to everyone on the planet. This has led to projects like the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture in Saudi Arabia.

"We strongly believe that culture and cultural buildings are going to free the free spirit of this world," said Thorsen.

The firm has faced criticism for accepting a commission from an authoritarian regime. But Thorsen believes that architects have a duty to create buildings that improve the lives of citizens everywhere.

"We're making culture accessible in a place where it hasn't been," he said. "These border lines are difficult, but I've always believed that architecture is a great societal tool."

"That's why architecture needs to expand into these larger contexts of societal responsibility and it needs to be taken by those who have the insight, the education and the money."

Multi-disciplinary practice

In recent years, Snøhetta has expanded its practice beyond just architecture and landscape, into interiors, products and graphic design. Thorsen describes it as building up "a picture of the totality of the physical world".

With offices in four continents, the firm's diverse range of projects includes an underwater restaurant, a chair made from recycled fishing nets and graphics for Norway's national bank notes.

"We really believe in this total principle," added Thorsen. "It's about values, content, content innovation, performance, inclusion of a larger public, a feeling of unity, place, environment, technological development, etc."

"All these things come together in a huge complexity, and we're trying to solve them by cross-professional work," he continued.

Read on for an edited transcript from the first part of the interview with Thorsen. Part two will be published on Dezeen in the coming days.

Amy Frearson: How has the way Snøhetta works changed over the past 30 years?

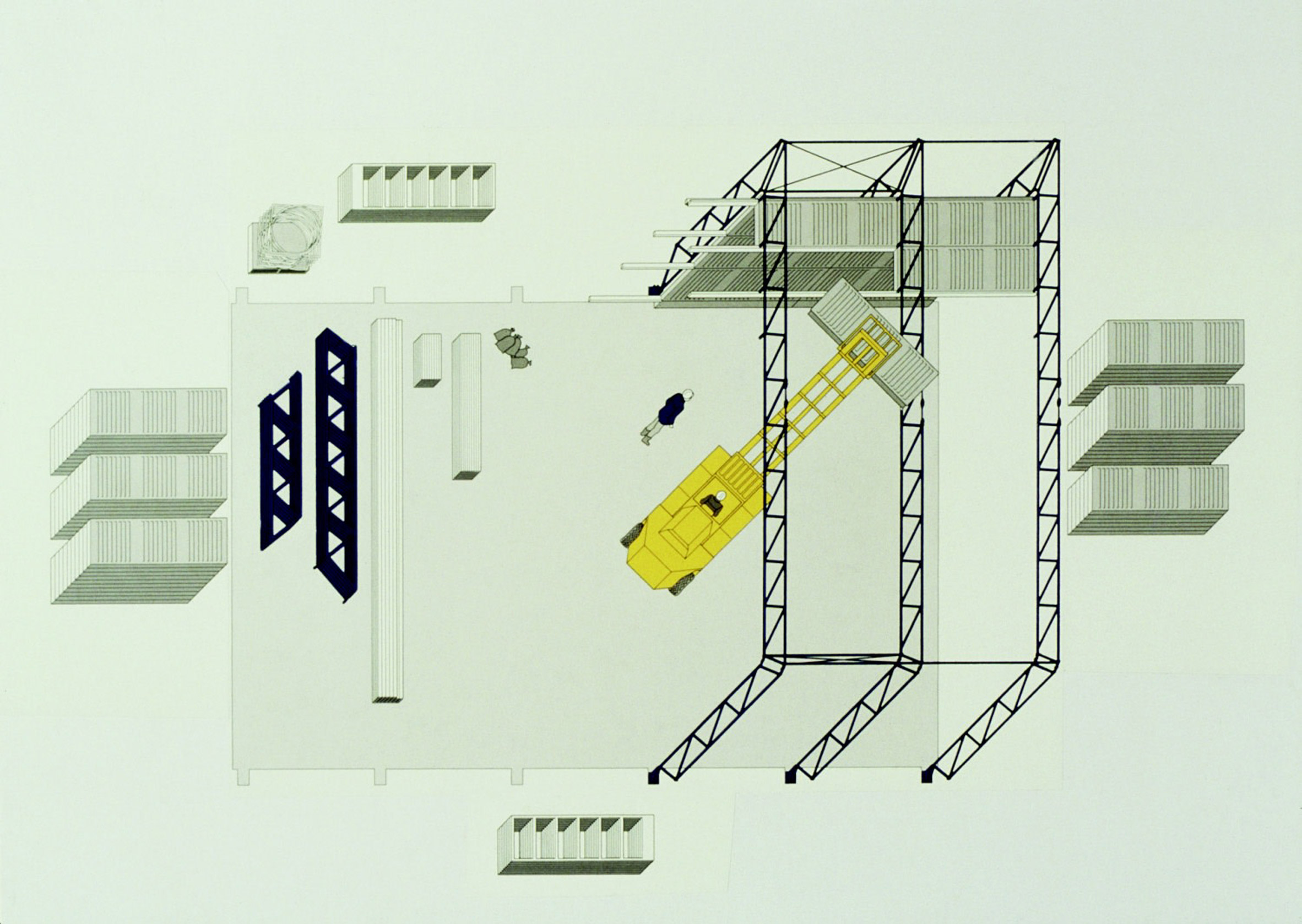

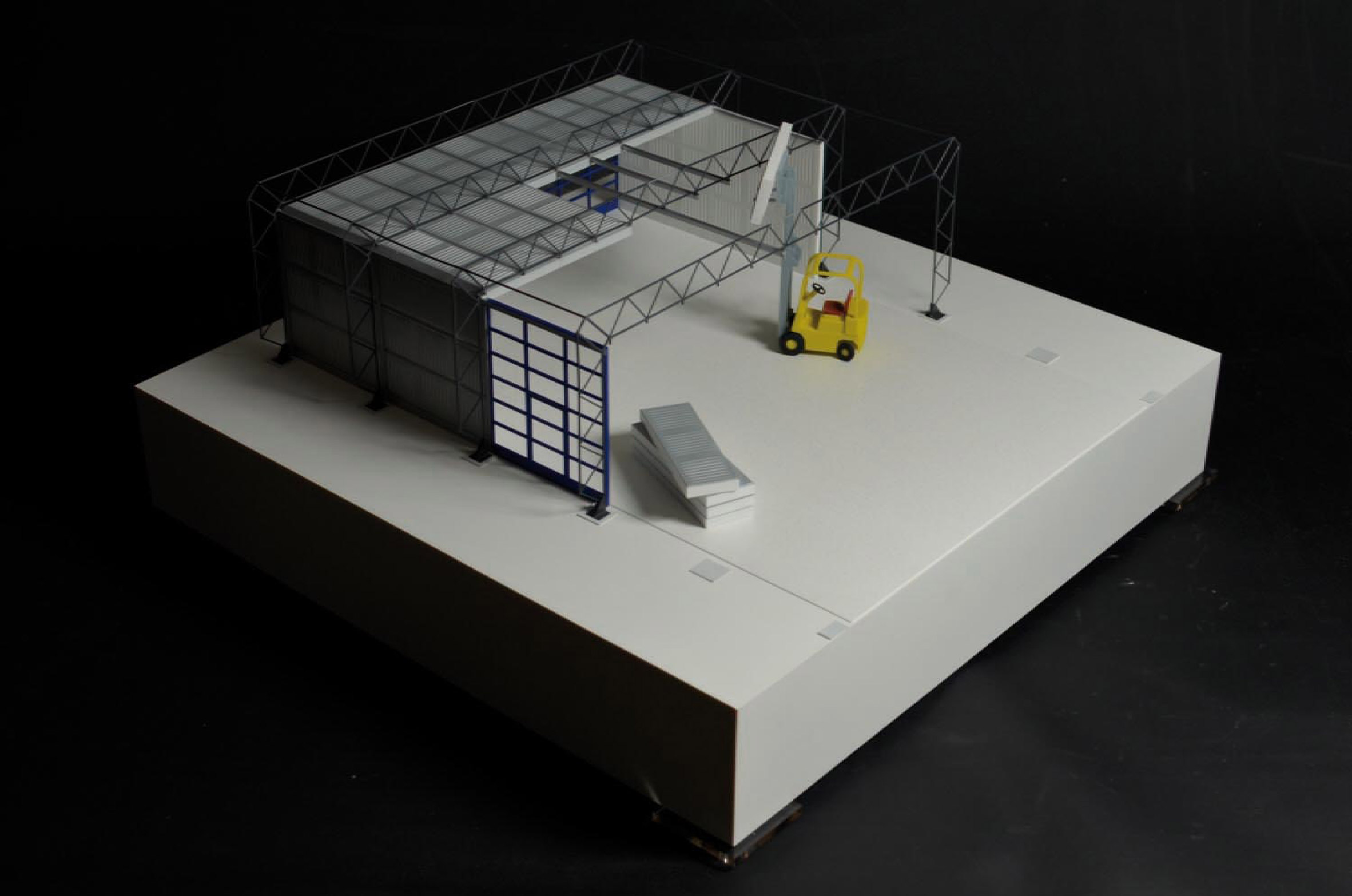

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: When it comes to everything that has to do with technology. I feel like a dinosaur, in a way. When we drew the Alexandria library, of course it was by hand. There were no renderings, no BIM. It feels like a different life and so distant from everything that we're doing at the moment.

Amy Frearson: Has technology changed your approach to design?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Completely. Tools change how you perceive things, what you do and how you work with them. You have to reinvent yourself continuously because of time and changes around you. At the same time you change yourself. So you follow this kind of change both ways. Major change is really how the profession operates in relationship to its own tools, in relationship to clients and in relationship to the different markets that you're working with.

We were lucky that one of our first projects was in Egypt. We were in a position where we had to listen, to find out what was happening in the local environment in Alexandria. We had to be contextual from the very beginning.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me about that first project and the early days of Snøhetta? How did the studio start?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: In 1987 we had a very loose constellation of landscape architects and architects. We started with both professions from the very beginning. There is an area in Norway called Dovre, which is a mountain area, and the highest peak is called Snøhetta. And because we established ourselves in the attic above a beer place in Oslo, called the Hall of Dovre, we called ourselves Snøhetta.

In 1989, we won the competition for the library in Alexandria. We had been testing ourselves in Norway on quite a few competitions, but were only ever getting second or third place. We didn't seem to win anything. I think we were pushing the borders too far at the time. At that same time, we also opened the architecture gallery ROM, which was pushing exhibitions as an inspiration for the local community of architects and artists, pushing the representation of international names in Oslo.

Amy Frearson: What do you mean when you say pushing too far?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Design-wise, the concepts that we were developing at the time were coming out of this constellation of landscape architecture and architecture. So many of them already had this intersection with the water, up and over. It was a lot of stuff.

We had a very introverted architectural scene, very traditional, very organised, very solid crafting. The average level of architects was quite high and we had some really great offices, but there was no inspiration of moving into any other kind of things, beyond the Norwegian tradition for very beautifully crafted, straightforward architecture. We were a little younger and we had different design ambitions, maybe.

So we set up an office in LA. It was a temporary office. We rented an apartment and got equipment from film studio rental places.

Amy Frearson: Why did you choose LA?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: I had friends there, Christoph Kapeller and Craig Dykers, who became my partner. So we set up a studio there to design the Alexandria library. It was nice getting away, doing it differently, not being in an office in Oslo under a different latitude. LA was interesting. We spent five weeks there, then we moved back to Oslo and then we won the competition.

Amy Frearson: So when you won the competition for the Alexandria library, you hadn't built anything else?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: No. So we established a shareholding company with a larger group of people. Then we were struggling for four years to sign the contract of that competition that we won.

Amy Frearson: So the project ended up taking quite a lot of time? You had time to establish your office in the meantime?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: We were working on it from 1989 until 2000, but the official opening was in 2002. Everything was a little chaotic. But one of the things that I don't regret is that it did take so much time, because I couldn't imagine having to jump into it with an unexperienced team who had never built anything. One of these high-speed Chinese projects would be impossible for a new office, established based on a competition. So at least we had time to build both skills and organisation.

We relocated to Cairo for almost a year and a half, with 14 people and kids and families, which we did from 1993 to 1995. We actually did the design in Cairo with our local engineering partner. We had to educate young stonemasons to be able to carve a granite wall. We opened a quarry. It was very much hands-on architecture. We were following every piece of the building, from A to Z, on site.

In a way, it was something that opened up the possibility of combining this landscape and architectural practice. It was maybe the first understanding of how an architectural concept could be contextualised. Could this library have been designed for anywhere else? No, most likely not. It was for this very particular site in Alexandria, depending on the very precise north-east-west situation to get indirect light into the space, and protected against the sound from the south. All of these things started coming together as a very specific kind of idea.

From then on, a lot of things started spiralling, more or less by coincidence. In 2000 we won the Opera House. So there was a 12-year project, awaiting an eight-year project. Two projects over 20 years, although of course there were a lot of other projects happening in between. Then in 2005, the Ground Zero Memorial and expanding into New York, and in 2008, the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture.

Amy Frearson: So you see these projects as defining very distinct chapters in your history?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: Yes. After that things started rolling and expanding, and we also expanded our disciplines. We had interiors, landscape and architecture, then expanded with graphic design and product design. We were trying to get this picture of the totality of the physical world.

Amy Frearson: So your original concept, this merging architecture and landscape, has also defined how Snøhetta as a practice has grown and developed?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: It came very naturally to us. Norway gave us a direct connection to nature obviously – it's a very unpopulated country, so even if you live in the city, you live in the countryside. But this combination also came out of necessity. We were seeing at the time that construction projects didn't have budgets for their outdoor areas. So it was like whatever was left over from the construction could be spent on the landscape.

We said that this can't be the case, because we're neglecting our public space. But if we combine the two, we can also combine the budget. So we can actually use the full construction budget also on the landscape. This is how we ended up at the Oslo Opera House, where there is no differentiation between public space, building and site.

Amy Frearson: Is this still a problem in architecture today, do you think? Do buildings still come before landscape?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: I think it's a big problem. Even in urban planning, we seem to plan objects first and then look at whatever is left. It's been a long-standing problem, with the western world's urbanisation, where everything is based on a grid system. That grid system came out of control. But we still love the typology and we keep developing cities as if we didn't have democracies.

Amy Frearson: What principles and values has Snøhetta held onto over the past 30 years?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: I think you have to remember that 1989 was the time when sustainability was defined into the UN for the first time, with our former prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland's definition of social, environmental and economical sustainability. I think we grabbed and held on to the social sustainability part of that, by trying to create buildings where there was no differentiation between the aesthetics of something and its social sustainability. We were trying to create buildings that could generate some sort of public ownership – like libraries and concert houses – by changing the attitude towards them. We strongly believe that culture and cultural buildings are going to free the free spirit of this world.

We started off, I think, very clearly with a picture of how architecture could contribute to better social awareness, but not necessarily out of the position of a third-world country or a western-world country, but more based on questions. Like when we were doing the Alexandria library, we asked, why would you design such a big, expensive library in a city where 50 per cent of the population is illiterate? The answer was, well that's why. That's maybe also why Ground Zero was such an important breaking point for us. It was bringing a site of big trauma back into an everyday situation.

The same goes in places like Saudi Arabia. We're still receiving criticism about working in Saudi, especially after Khashoggi, it's become much tougher. But we're trying to talk to a very young generation of Saudis who are extremely curious. There is a fairly big underground scene when it comes to film, literature, art. We're making culture accessible in a place where it hasn't been.

Amy Frearson: How do you deal with working in places like Saudi, where the situation is so fundamentally different?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: These border lines are difficult, but I've always believed that architecture is a great societal tool. Architecture is not like art. You can accept art in its own right, but architecture has a different kind of position. That's why architecture needs to expand into these larger contexts of societal responsibility and it needs to be taken by those who have the insight, the education and the money.

And in a way, you get to this point where you say, If you really believe this kind of total principle, then the values, the content, the content innovation, the performative aspects of it, the inclusion of a larger public, the feeling of unity, place, environment, technological development, structural, what kind of materials are you using, how lightweight can you actually construct a building with endless kind of choice of materials.

So all these things come together in a huge complexity. And for us, it's trying to solve it by cross professional work. In the future, where these groups of different disciplines are highly specialised and bring them to the table that can be very generous. And then transposition between the different professions and then see how we can work within the creative industry and actually giving real solutions.

Amy Frearson: What are going to be Snøhetta's big focuses going into the future?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: This notion of maintaining and enhancing our social responsibility is still on the move, and this urban planning notion from an architectural perspective. What does that mean for the objects of communal living, for bottom-up and top-down processes?

We really believe in this total principle. It's about values, content, content innovation, performance, inclusion of a larger public, a feeling of unity, place, environment, technological development, etc. All these things come together in a huge complexity, and we're trying to solve them by cross-professional work.

The post Merging architecture and landscape "came very naturally" to Snøhetta says co-founder appeared first on Dezeen.

from Dezeen https://ift.tt/2siXfl6