To conclude our high-tech architecture series, we round up everything you need to know about the movement from A to Z.

A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

A is for Anthony Hunt

Anthony Hunt is a structural engineer who was key to the success of many of the most-prominent high-tech buildings and worked with all of the leading British proponents of the style – Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Michael and Patty Hopkins and Nicholas Grimshaw.

His best-known high-tech projects include the Reliance Controls factory, Hopkins House, the Sainsbury Centre and the International Terminal at Waterloo station.

B is for B&B Italia

High-tech architects Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano collaborated together throughout the 1970s on a series of factories and offices including the headquarters of furniture company B&B Italia in Como, Italy.

Built in 1973, the office is described by the furniture brand as "a real-scale prototype" for the Centre Pompidou, which would complete four years later.

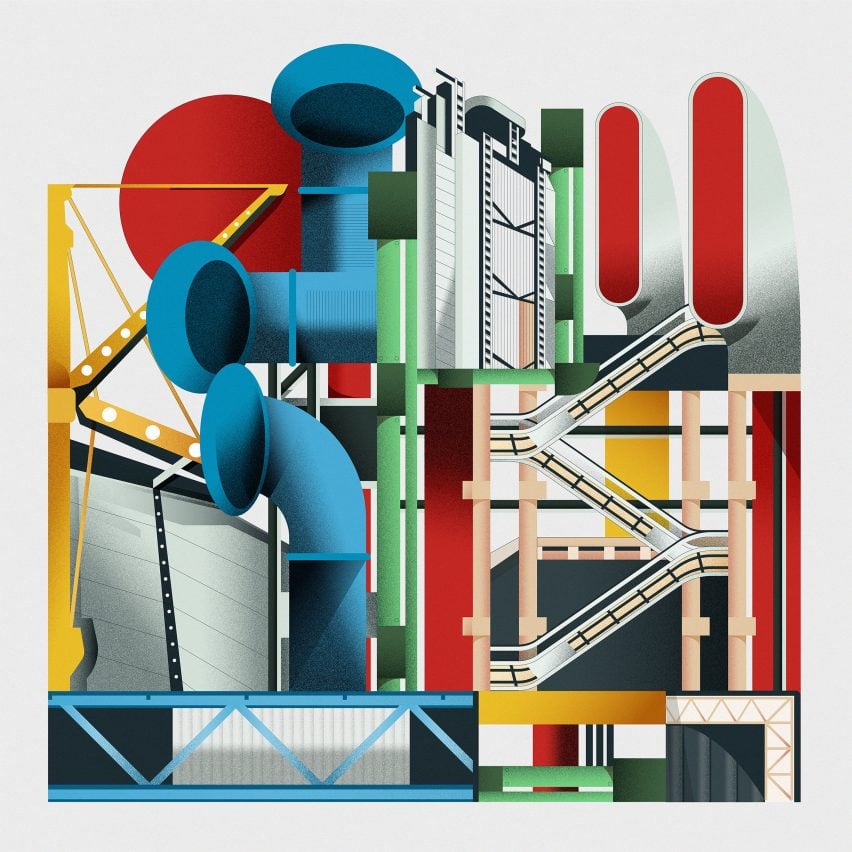

C is for Centre Pompidou

Designed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, the Centre Pompidou is one of the most significant buildings of the high-tech style and helped draw global attention to the movement.

Completed in 1977, the cultural landmark is a clear example of an inside-out building, with its structure and mechanical services visible on its exterior.

D is for Millennium Dome

The Millennium Dome, which is the largest domed-shaped tensile structure in the world, was created by the Richard Rogers Partnership to house a festival marking the year 2000.

Effectively a giant tent, the dome's structure is supported on twelve bright-yellow, one-hundred-meter high steel masts.

E is for Eden Project

Completed in 2001, the Eden Project is one of Nicholas Grimshaw's later high-tech highlights.

The tourist attraction turned a Cornish clay pit into an international attraction with a series of interlinking giant domes containing a climate-controlled environment for 5,000 varieties of plants.

F is for Factories

Many of the early high-tech buildings were factories, with Team 4's Reliance Controls factory being one of the first recognisable buildings of the movement.

Other significant high-tech factories include the Herman Miller Factory (pictured) designed by Nicholas Grimshaw, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano's UOP Factory and Rogers' Inmos Microprocessor Factory

G is for Nicholas Grimshaw

Nicholas Grimshaw is one of high-tech's most significant architects. With a career lasting more than 50 years, he has built numerous structures that demonstrate the key ideals of the style.

His early high-tech highlights include the Park Road Apartments and Herman Miller Factory, both designed with Terry Farrell, with his later buildings including the International Terminal at Waterloo station and the Eden Project.

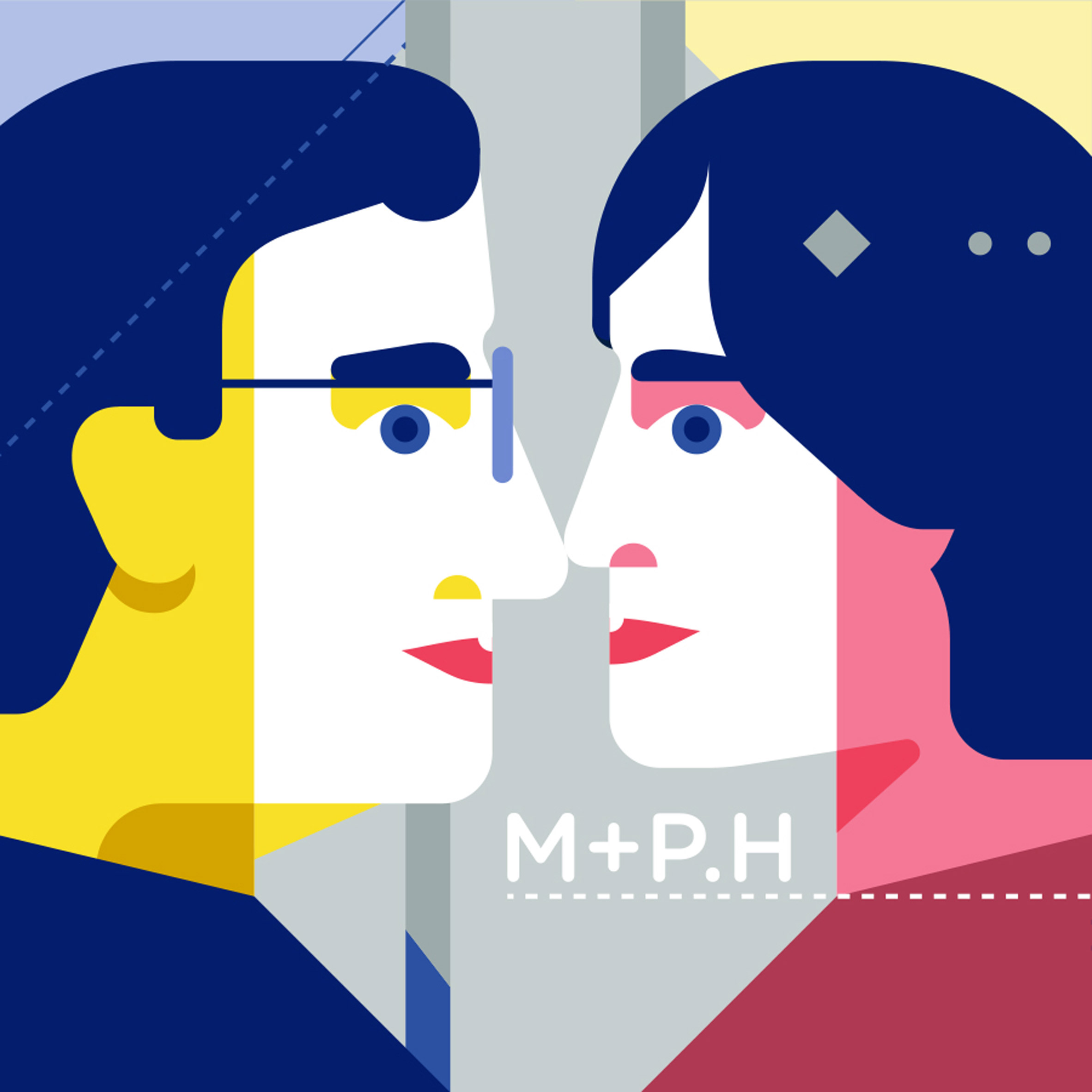

H is for Michael and Patty Hopkins

Michael and Patty Hopkins' first project together was one of the high-tech architecture's most pragmatic buildings – Hopkins House.

The husband and wife couple would go on to develop historicist high-tech architecture, designing buildings including the Mound Stand at Lord's cricket ground and Portcullis House next to the Houses of Parliament.

I is for Inside-out buildings

Inside out was the name given to high-tech buildings that proudly display structure and mechanical engineering on the outside, rather than hidden within the building.

Two of the clearest examples of inside-out buildings are two of high-tech architecture's most significant structures – the Centre Pompidou and the Lloyds building.

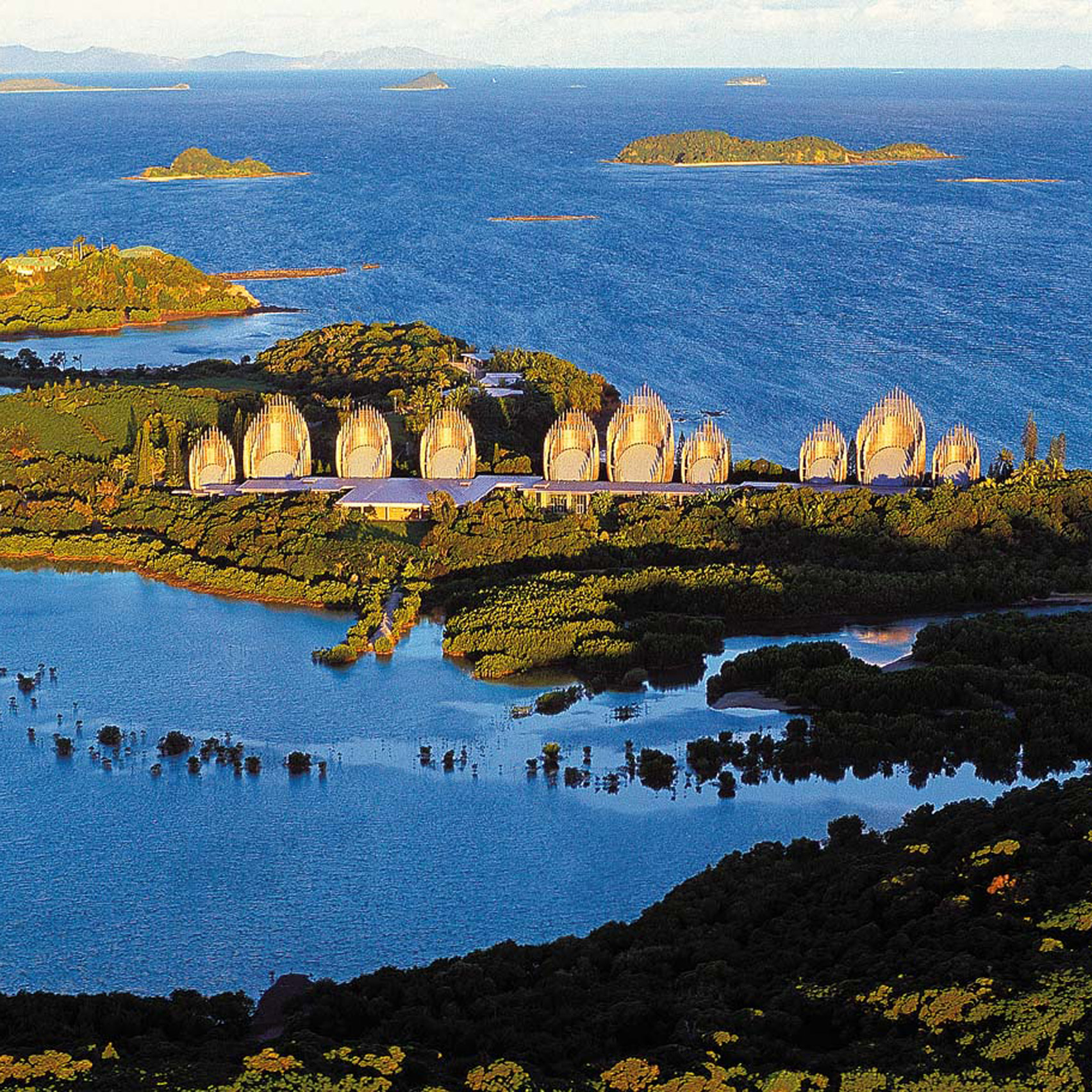

J is for Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre

Designed by high-tech architect Renzo Piano ,the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre in New Caledonia was completed in 1998. Named after an assented assassinated politician, the project on the pacific island combines high-tech with local building traditions.

K is for Kansai airport

Built on an artificial island in Osaka Bay, Japan, the Renzo Piano-designed Kansai International Airport has a mile-long terminal with an asymmetrical clear-span roof.

The structure of this roof is clearly visible from within the terminal.

L is for Lloyds building

One of the most significant and recognisable pieces of architecture created in the 1980s, the Lloyds building demonstrates many of the key traits of the high-tech architecture style.

Designed by Richard Rogers, the building's radical inside-out aesthetic creates clear, open spaces for offices inside.

M is for Inmos Microprocessor Factory

The Inmos Microprocessor Factory was one of the numerous high-tech factories built in the UK during the 1970s and 80s.

Like much of Richard Rogers' high-tech architecture, the building's structure is placed on the outside to create large column-free spaces within the factory.

N is for Norman Foster

Norman Foster is perhaps the best known of the high-tech architects.

He has created buildings in the high-tech style for five decades, with highlights including Reliance Controls in the 1960s, the Sainsbury Centre in the 1970s, the HSBC building in the 1980s, Stansted Airport in the 1990s and the Gherkin in the 2000s.

O is for Open plan

High-tech architecture used structural engineering and materials like steel to create buildings with large column-free spaces. In the numerous high-tech offices and headquarters, including the Willis Faber & Dumas building, these spaces were used as open-plan office space.

"I remember the opening day in Willis Faber," Norman Foster recalled in an interview with Dezeen. "And I can even remember the guy who was running it, Ronnie Taylor – this is going back to the 1970s – he insisted on having his own enclosed office. On the first day, he instructed for it to be taken down."

P is for Renzo Piano

Italian architect Renzo Piano was the leading non-British proponent of the largely British-led high-tech architecture movement.

He designed one of its most seminal buildings, the Centre Pompidou, along with numerous other structures including Kansai airport and the B&B Italia headquarters.

Q is for Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation HeadQuarters

While not many high-tech buildings begin with a Q, there have been numerous corporate headquarters built in the style. The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters was one of the earliest and most significant.

The ground-breaking skyscraper in Hong Kong established Norman Foster as a global brand.

R is for Richard Rogers

First as part of Team 4, then in partnership with Renzo Piano and finally at his own practice, Richard Rogers designed many of high-tech architecture's most significant and recognisable structures, such as Centre Pompidou and the Lloyds building.

S is for Sainsbury

Two of high-tech's most significant buildings bear the Sainsbury name.

The Sainsbury Centre was designed by Norman Foster to house the art collection of Robert and Lisa Sainsbury at the University of East Anglia in Norfolk, while Nicholas Grimshaw designed an overtly functionalist supermarket for Sainsbury's in Camden, London.

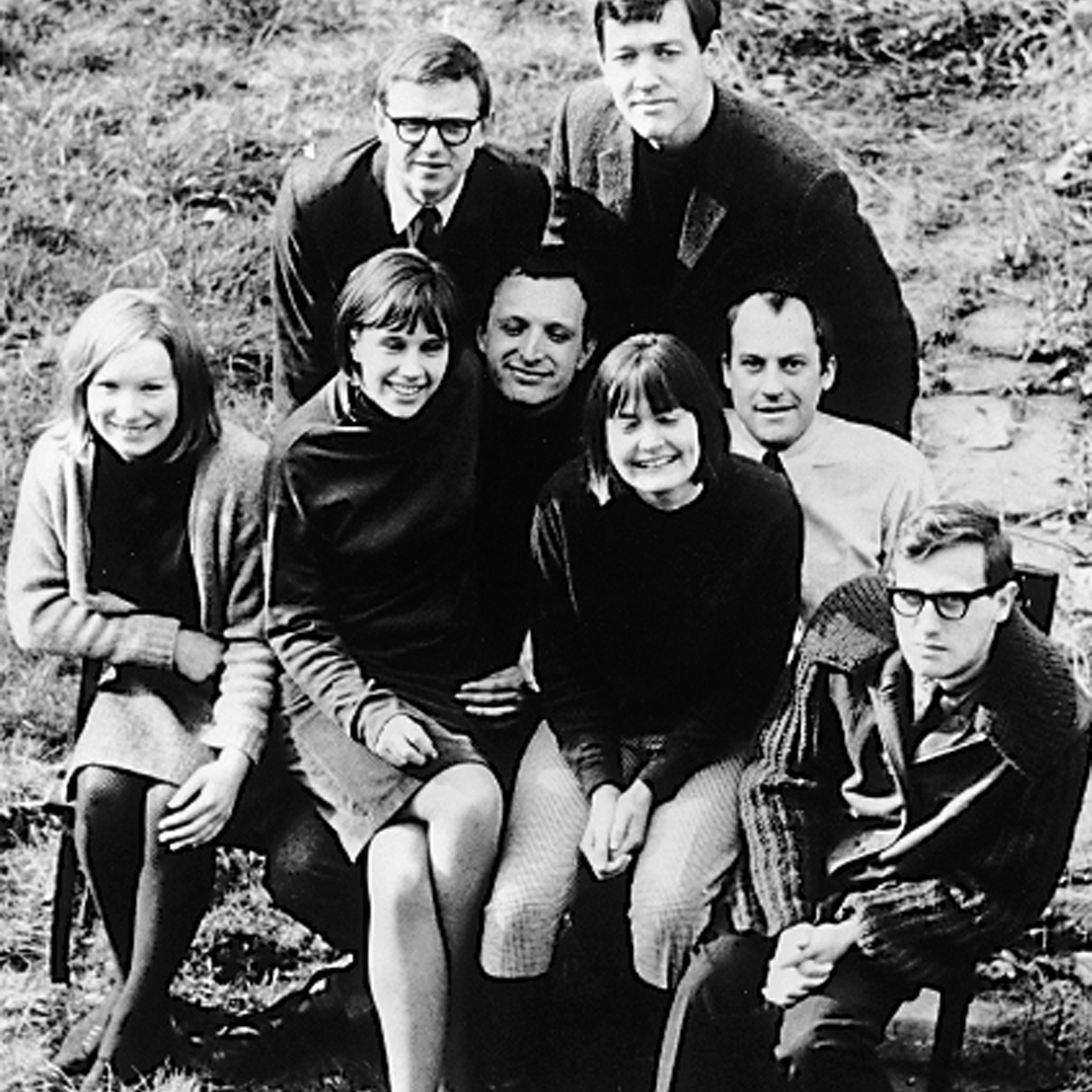

T is for Team 4

The group known as Team 4 – Su Brumwell, Richard Rogers, Wendy Cheesman and Norman Foster – began to develop the ideals of high-tech architecture in the UK.

Established in 1963, the group only completed a handful of projects, the most significant of which was its last building, the Reliance Controls factory in Swindon.

U is for UOP Factory

The UOP fragrances factory in Tadworth, UK, is one of several projects completed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano during their partnership in the 1970s.

The one-storey factory was designed to be extremely flexible and is clad in large panels of glass-reinforced concrete (GRC) that could be removed if needed. It is currently unused and reportedly under threat of demolition.

V is for Creek Vean

Creek Vean was the first major project undertaken by Team 4. The architecture group that comprised Su Brumwell, Richard Rogers, Wendy Cheesman and Norman Foster would go on to build the Reliance Controls factory, which many consider the first high-tech building.

Built for Brumwell's parents, the house is made from honey-coloured concrete blocks.

W is for Willis Faber & Dumas

Norman and Wendy Foster's first major commission after they established Foster Associates, the Willis Faber & Dumas building is a revolutionary office block in Ipswich, which was completed in 1975.

The three-storey block, which occupies its entire site, is wrapped in a glass curtain wall and contains open-plan office space.

X is for X-bracing

One of high-tech architecture's key features is its visible structure that often includes cross bracing. It is clearly visible on one of the earliest high-tech buildings, the Reliance Controls factory.

"It's about the diagonals. It's about the cross bracing," said Norman Foster in a video interview with Dezeen. "It's about showing what is holding the building up, pushed to a metallic extreme."

Y is for yellow

Bold primary colours were used to highlight the structural elements in many high-tech buildings.

Bight yellow was the colour of choice at Norman Foster's Renault Distribution Centre, Nicholas Grimshaw's Igus Factory and Richard Rogers' Millennium Dome.

Z is for Žižkov TV Tower

The Žižkov Television Tower is a high-tech transmitter tower positioned at the top of a hill in Prague that soars over the city's otherwise historic and traditional skyline.

Completed in 1992, the tower by Václav Aulický is based on a triangle with corners that extend upwards as steel, concrete-filled columns, from which nine pods and three decks for transmitting equipment are suspended.

Main illustration is by Jack Bedford.

The post High-tech architecture from A to Z appeared first on Dezeen.

from Dezeen https://ift.tt/2TmbAIH