The London-based cinematographer who has worked for the likes of Nike, Adidas, WePresent and Valentino, talks us through two of her recent projects.

from It's Nice That https://ift.tt/2x2rSy7

The London-based cinematographer who has worked for the likes of Nike, Adidas, WePresent and Valentino, talks us through two of her recent projects.

The Berlin-based graphic designer talks us through three recent (and very, very nice) projects.

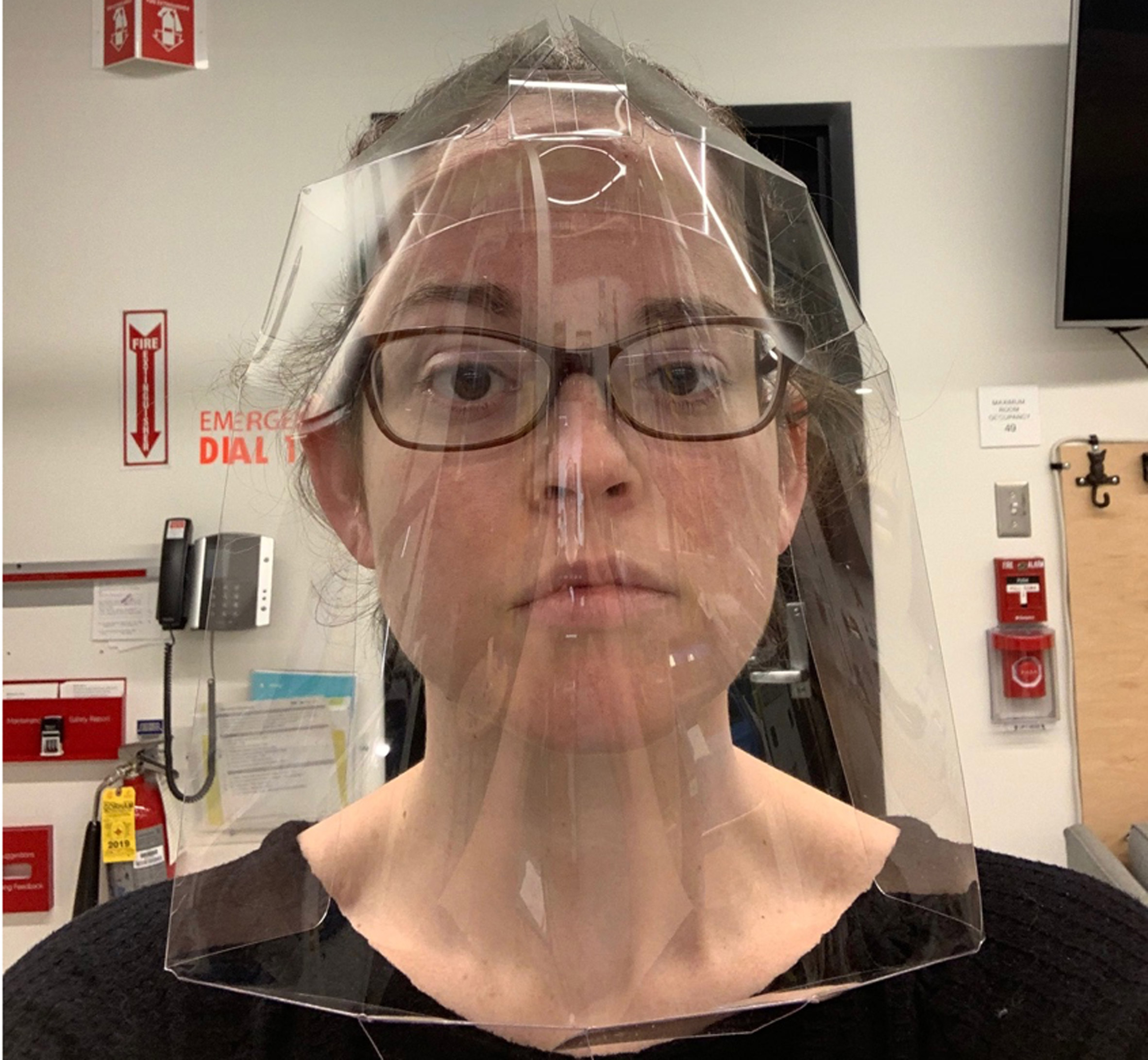

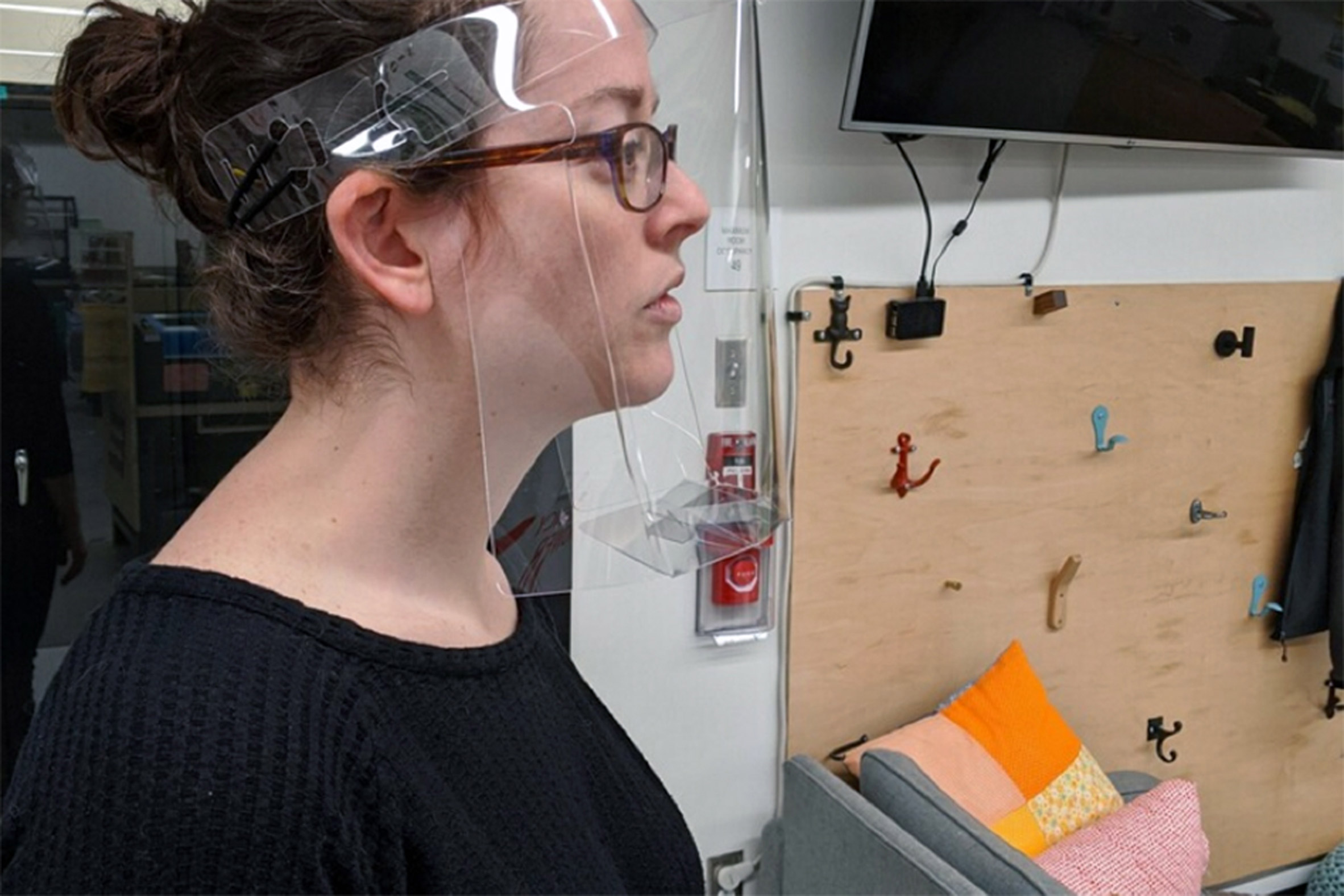

Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers have begun mass-producing disposable face shields for medical workers fighting Covid-19, which come flat-packed and can be folded into shape.

In a bid to meet the increasing demand for personal protective equipment (PPE) amid the coronavirus pandemic, a team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have designed disposable face shields that can be rapidly mass produced.

Made from a single piece of plastic, each shield comes in a flat design that can be swiftly folded into a three-dimensional structure when needed for use.

The face shields also offer additional protection with flaps that fold under the neck and over the forehead.

After testing a few materials that cracked and broke when bent, the team landed on the polycarbonate and polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG) materials.

"When you're thinking of materials, you have to keep supply chains in mind," said Martin Culpepper, professor of mechanical engineering and project leader.

"You can't choose a material that could evaporate from the supply chain," he added. "That is a challenging problem in this crisis."

The face shields are made from singular pieces of polycarbonate

Each single-piece shield will be made using the die-cutting process. Machines cut the design from thousands of flat sheets per hour.

These will then be sent in their flat form to hospitals, where doctors, nurses and other frontline health care workers can quickly fold them into their three-dimensional form before adjusting them to their face.

According to MIT, the die-cutter machines used in mass production would be able to make 50,000 of the flat face shields per day.

"These face shields have to be made rapidly and at low cost because they need to be disposable," explained Culpepper.

"Our technique combines low-cost materials with a high-rate manufacturing that has the potential of meeting the need for face shields nationwide," he added.

To assemble the masks, first the protective film must be peeled away from both sides of the flat face shield.

The top strip can then be folded over to make hard creases, before folding down the visor elements to make the cover and then the side and bottom flaps.

Following this, cuts on each side of the tab coming from the top of the shield can be slotted into the two tabs positioned either side of the shield's main body.

Hair ties or rubber bands can then be attached to secure the structure into place.

MIT's plan to mass-produce the one-piece shields – labelled Project Manus – was initiated in an attempt to help fulfil the high demand for tens of millions of disposable protective equipment that will be required in the US each month.

As the team explained, when used correctly face masks should be changed every time a medical worker treats a new patient.

But due to shortages during the coronavirus pandemic, they have been asked to wear the same one all day.

"That one mask could carry virus particles – potentially contributing to the spread of Covid-19 within hospitals and endangering health care professionals," said the designers.

The clear face shields, shaped like a welder's mask, address this problem by providing another layer of protection that covers the wearer's entire face including the mask, to extend the life of PPE.

"If we can slow down the rate at which health care professionals use face masks with a disposable face shield, we can make a real difference in protecting their health and safety," explained Culpepper.

Initial fabrication of the shields was begun this week by Boston-based plastic product manufacturer Polymershapes, and the company plans to expand across the country to 55 additional locations.

"This process has been designed in such a way that there is the potential to ramp up to millions of face shields produced per day," said Culpepper. "This could very quickly become a nationwide solution for face shield shortages."

The first 100,000 shields, which are due to be made and shipped this week, will be donated to local Boston-area hospitals by Polymershapes and MIT.

Beyond these initial donations, those in need of the face shields for Covid-19-related use can fill out a request form online.

MIT is also providing the design of the face shields free of charge to verified professional die cutters, and the team has created a form for requests from companies who are interested in obtaining the fabrication files.

The post MIT develops one-piece plastic face shields for coronavirus medics appeared first on Dezeen.

A huge faux staircase interrupts the floor plan of this house in Tokyo, which design studio Nendo has created for three generations of the same family.

Stairway House is situated in a quiet residential pocket of Shinjuku, a ward of Tokyo known for its neon-lit buildings, bustling streets and vibrant nightlife scene.

The three-storey home is designed to accommodate three generations of the same family. It replaces a smaller, timber-framed property that had become overshadowed by surrounding apartment buildings.

Nendo constructed the new house in a brighter spot at the northern end of the site, being careful to preserve a mature persimmon-fruit tree that was planted by previous occupants.

The more accessible ground floor has been designated to the older couple in the family and their eight pet cats, while the upper two floors of the house have been given to the younger couple and their child.

To prevent the two parties from feeling isolated in their respective living quarters, the studio decided to erect a sweeping staircase-like structure that unites every level of the home.

It runs from the back garden, through the glazed rear facade and right up to the top floor.

Steel has been used to craft the portion of the structure that's inside Stairway House, while concrete was used to make the outdoor steps.

"Not only does the stairway connect the interior to the yard, or bond one household to another, this structure aims to expand further out to join the environs and the city," Nendo explained.

A small playroom for the cats and bathroom facilities are hidden within the structure, as well as an actual staircase that can be used to access the home's higher floors.

The external steps – including those in the gravelled garden – have been dotted with an array of leafy potted plants. Nendo included this feature to evoke the feel of a greenhouse.

The steps also serve as a comfy, sun-soaked lounge spot for the cats throughout the day.

Some of the glazed panels in the gridded facade can also be pushed back to fill the interior with fresh air.

A restrained approach has been taken to decorating the rest of Stairway House.

The majority of the furnishings, such as the breakfast island in the kitchen and study desk, are jet black.

Tall storage shelves are integrated into the white walls, so that inhabitants can neatly stow away their belongings.

Even the front facade of the home has been kept simple: it's completely windowless.

Nendo is a multidisciplinary design studio with offices in Tokyo and Milan. Recent work includes a kinetic installation made up of blossom-like raindrops and a clock that morphs into the shape of a perfect cube twice a day.

Stairway House is not the only project to make faux stairs a focal point – last year, Beta Ø Architects inserted a dramatic stepped sculpture into the central void of a home in Madrid.

The post Steel and concrete steps cut through facade of Stairway House by Nendo appeared first on Dezeen.

UK charity Art Fund's crowdfunding campaign to save artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman's cottage in Dungeness from being sold to a private owner has been successful.

The Art Fund has raised £3,624,087 to purchase Prospect Cottage in Kent, which was at risk of being sold to a private individual, from the Keith Collins Will Trust.

The house will now be taken care of by arts organisation Creative Folkestone, which will organise a permanent public programme and conserve the building including its renowned wild garden sown on the beach shingles.

For the first time, the public will now be able to view the interior of the house, which was a source of inspiration and creative hub for the artist who bought it in 1986.

Jarman's archive of notebooks, drawings and sketches from the cottage will be on a long-time loan to Tate Archive and available to see at Tate Britain.

According to Art Fund it is the largest-ever arts crowdfunding campaign, receiving over 8,000 donations from the public as well as funding from charities, foundations, trusts and philanthropists.

"Securing the future of Prospect Cottage may seem a minor thing by comparison with the global epidemic crisis which has recently enveloped all our lives," said Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar.

"But Derek Jarman’s final years at the cottage were an inspiring example of human optimism, creativity and fortitude battling against the ravages of illness, and in that context the success of this campaign seems all the more apposite and right for its time."

Jarman moved to the house near the Dungeness nuclear power station after being diagnosed as HIV positive. He passed away from the illness in 1994 and bequeathed the cottage to Keith Collins, his close companion, who died in 2018.

The house is where Jarman shot his film The Garden, and his remarkable own garden at Prospect Cottage was the subject of his last book, Derek Jarman's Garden.

Since it launched on January 22, the campaign to save the cottage received donations from 40 countries around the world, with artists and advocates, including Peter Doig, Wolfgang Tillmans and Tilda Swinton, donating artworks and experiences to help raise the money.

The National Heritage Fund gave £750,000. The Art Fund and the Linbury Trust also supported the campaign with grants of £500,000 and £250,000, respectively. Artist David Hockney made a "substantial personal donation," Art Fund said.

Dungeness is home to a number of interesting architectural holiday homes, including the Black Rubber Beach House and a world war two pumping station.

The post Derek Jarman's Prospect Cottage saved by Art Fund campaign appeared first on Dezeen.