Architecture studio ABIBOO has designed the concept for a self-sufficient city on Mars named Nüwa that could be built in 2054. Its architect explains the project to Dezeen.

Set within a cliff on Mars, Nüwa was designed for non-profit organisation the Mars Society to be the first permanent settlement on Mars.

The vertical settlement, which could eventually house 250,000 people, would be embedded into the side of a cliff and built using materials available on the planet.

ABIBOO founder Alfredo Munoz believes that building a permanent, large-scale habitat on Mars is feasible this century and that the planet may have more potential for settlement than the moon.

"Permanent habitats on the Moon that are self-sufficient would be challenging, including the lack of water and critical minerals," he told Dezeen.

"On the other hand, Mars offers the right resources to create a fully sustainable settlement."

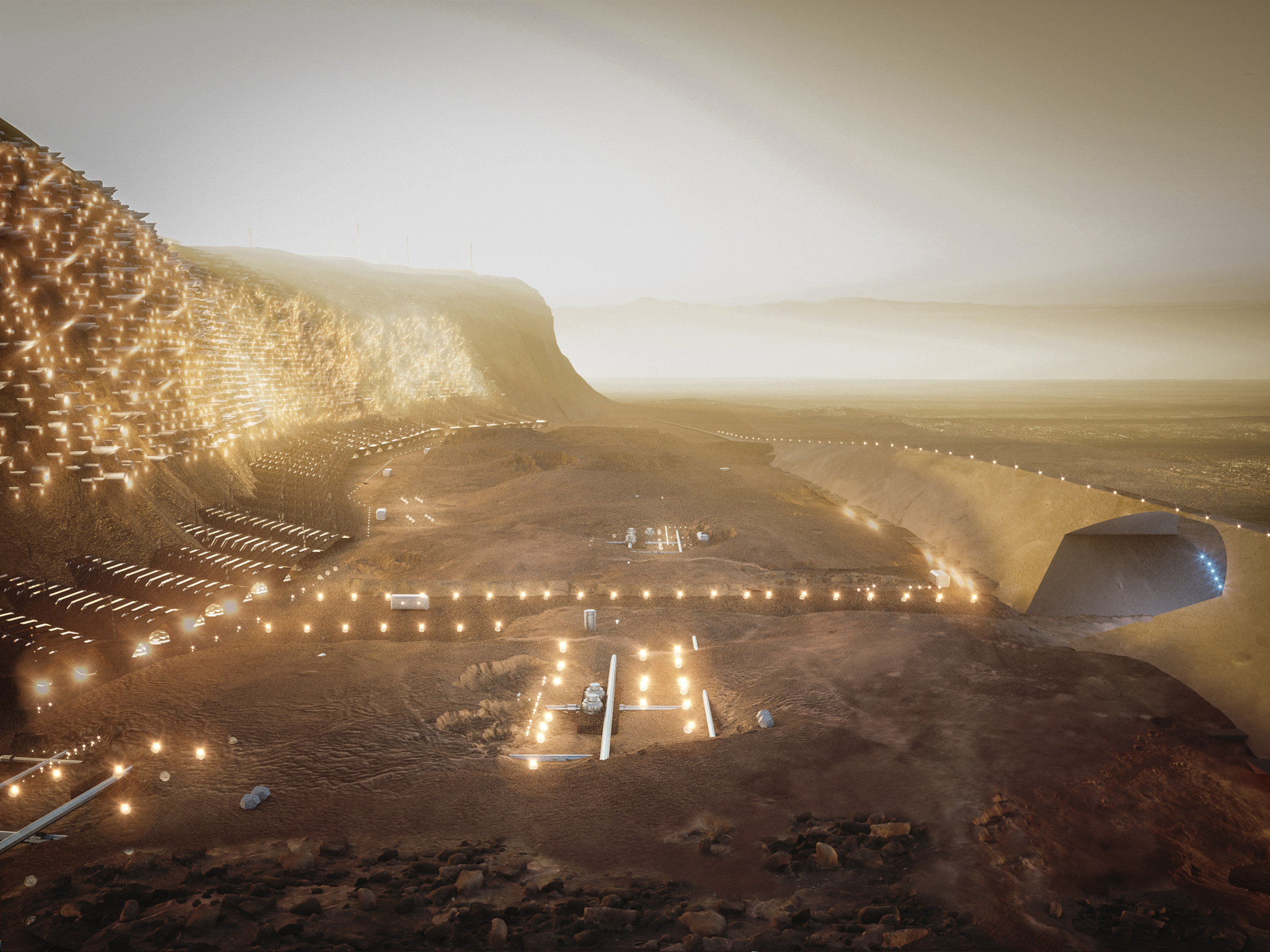

The city, developed with scientific group SONet, would be built into a one-kilometre-high cliff face to protect the residents from radiation and allow for a large city to be built without constructing huge enclosures.

"Nüwa solves all the core problems of living on Mars while creating an inspiring environment to thrive, architecturally rich and using only local materials sourced on Mars," said Munoz.

"It is a sustainable and self-sufficient city with a strong identity and sense of belonging. Nüwa is conceived to be the future capital of Mars."

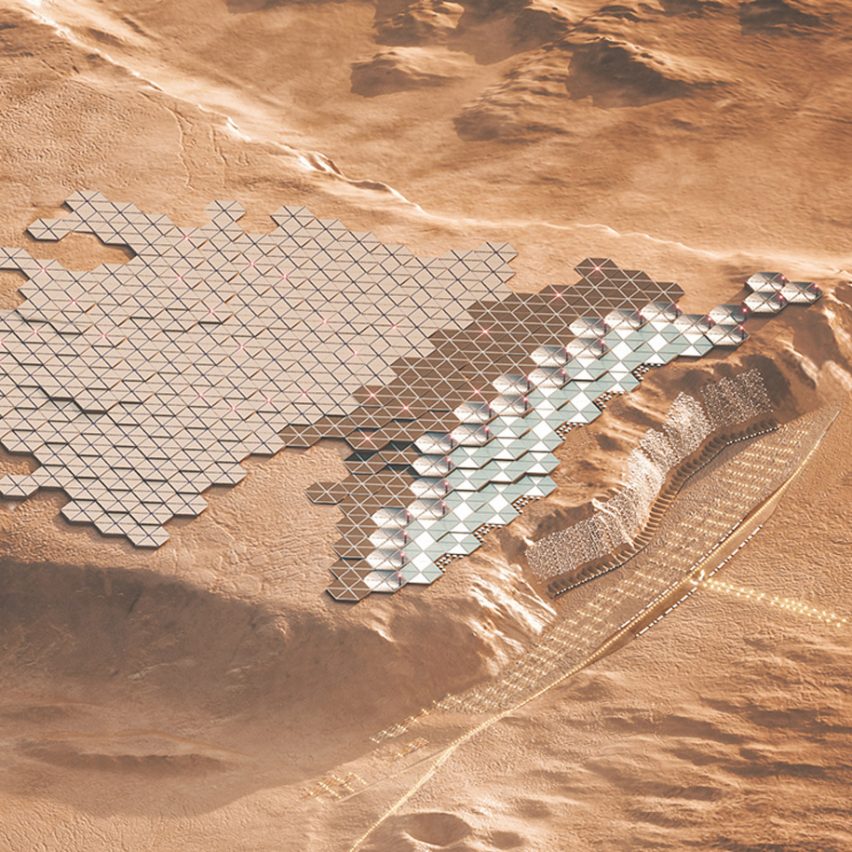

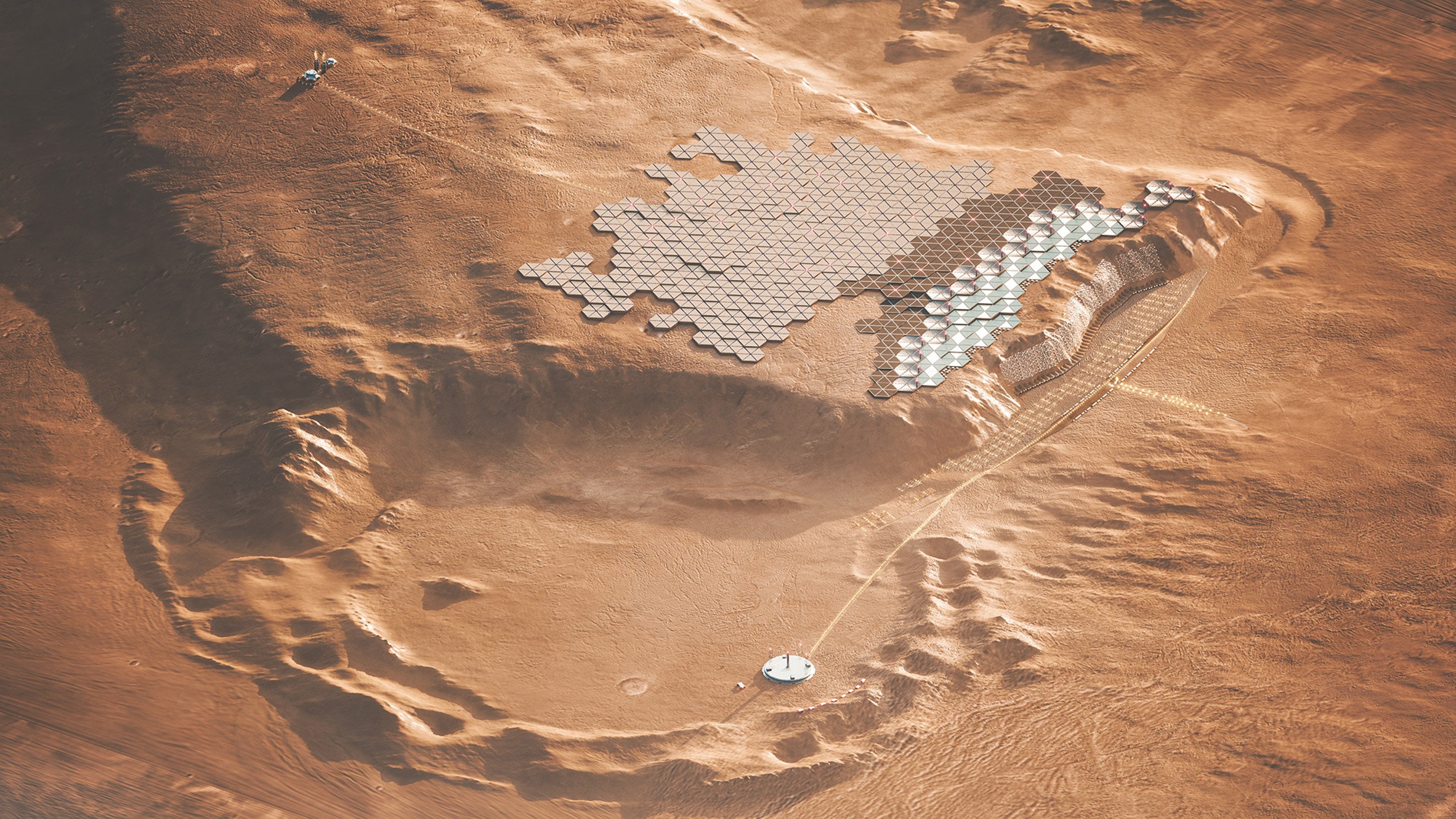

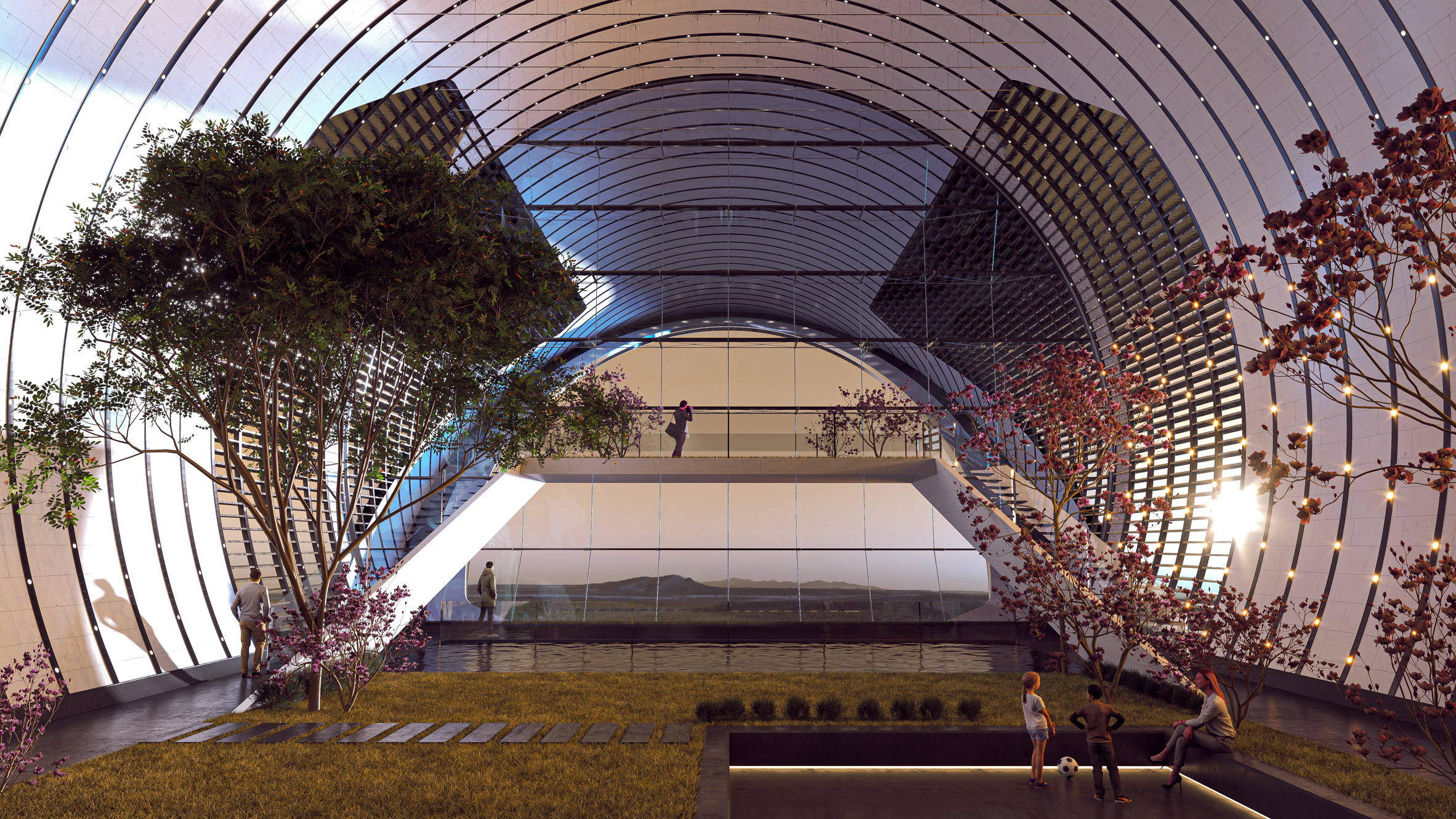

A system of interconnected tunnels would be bored into the Martian rock, with light entering from the cliff tunnel ends at the cliff face. The area at the top of the cliff would be used for growing food.

According to Munoz, Nüwa combines the benefits of previously proposed surface and tunnel dwellings.

"Some past solutions for habitats on Mars propose exciting buildings on the surface of the red planet," he said.

"The challenge with these solutions is that to protect effectively and long-term from radiation, the buildings' skin needs to be thick and opaque."

"Alternative past solutions on Mars are underground, located inside lava tubes or craters," he continued.

"Such building configurations might provide a more efficient and safe technical solution than those on the surface. However, access to light is essential for humans' phycological well-being, and spending long-term underground might not be the ideal solution."

ABIBOO's Martian city would be built using tunnelling technology that is"already available on Earth" and steel obtained by processing water and CO2 found on Mars using a system that will need to be developed.

While the studio believes that hydroponic systems for making food and solar generation systems for making electricity already largely exist, it sees manufacturing breathable air as the biggest technical hurdle to overcome to make the city viable.

The architect also highlights transporting goods and people to Mars and funding as potential barriers, but believes that construction could begin in 2054.

"We estimate that by 2054 we could be able to start building a settlement like Nüwa," Munoz said.

"However, this date is tentative as there are many critical paths associated with a city on Mars," he continued.

"If the right resources are in place and some of the required technologies on Earth support the speedy implementation, Nüwa could be finished by 2100."

Read on for the full interview with Alfredo Munoz:

Tom Ravenscroft: What is the core concept for Nüwa?

Alfredo Munoz: Nüwa is a vertical city inside a cliff. The town protects its inhabitants from deadly radiation, potential impacts from meteorites, and extreme temperature changes on Mars by this configuration. Additionally, its modularity provides a highly scalable solution that can be standardised while giving a very diverse experience to its citizens.

Nüwa solves all the core problems of living on Mars while creating an inspiring environment to thrive, architecturally rich and using only local materials sourced on Mars. It is a sustainable and self-sufficient city with a strong identity and sense of belonging. Nüwa is conceived to be the future capital of Mars.

Tom Ravenscroft: How does this differ from other prospective designs for living on Mars or the moon?

Alfredo Munoz: Permanent habitats on the Moon that are self-sufficient would be challenging, including the lack of water and critical minerals. On the other hand, Mars offers the right resources to create a fully sustainable settlement.

Some past solutions for habitats on Mars propose exciting buildings on the surface of the red planet. The challenge with these solutions is that to protect effectively and long-term from radiation, the buildings' skin needs to be thick and opaque.

Additionally, the pressure difference between the inside and the outside requires structures that prevent the building from exploding. For small buildings, this is not a terrible challenge because the design can absorb the pressure.

Still, the more ample space, the tension grows exponentially. As a result, on-the-ground-building is not reasonable to accommodate a large population, as the amount of material associated with their structure would be vast and expensive.

Alternative past solutions on Mars are underground, located inside lava tubes or craters. Such building configurations might provide a more efficient and safe technical solution than those on the surface. However, access to light is essential for humans' phycological well-being, and spending long-term underground might not be the ideal solution.

Nüwa is excavated on a one-kilometre-high cliff oriented to the south with tunnels that extend towards the cliff's wall, bringing indirect light and creating buffer spaces for the community to thrive and socialise.

Being inside the cliff protects from radiation and meteorites. The rock absorbs atmospheric pressure from inside and provides thermal inertia to avoid temperature losses, as the outside can be below 100 degrees Celsius.

Density is critical on Mars as every square meter is costly. Reducing the space required for infrastructure, logistics, and inter-city transportation is of utmost importance on Mars. The location of Nüwa inside a cliff ensures such space is minimised. Finally, the cliffs have a mesa at the top that is usually relatively flat, which is ideal for locating the vast areas required for the generation of energy and food.

Tom Ravenscroft: How did you aim to ensure that this is a feasible design?

Alfredo Munoz: Nüwa is the result of months of work of 30 plus global experts from different fields. ABIBOO headed the architecture and urban design. Still, the project's innovative solutions would have been impossible without the close collaboration with top global minds in astrophysics, life-support systems, astrobiology, mining, engineering, design, astrogeology, arts, and many other fields.

Tom Ravenscroft: What were the main factors that impacted the design of this concept?

Alfredo Munoz: The first factor was the Mars Society's request to provide a large-scale permanent settlement on the red planet. Creating a temporal solution or even a building for a small community of future Martian requires completely different strategies than those needed for a city where people will live and die.

Ensuring that the citizens have the right environment for an enriching life was critical for us. Public areas and vegetation are the core of life at Nüwa.

The second factor was our determination for Nüwa to be a self-sufficient and sustainable city on Mars. This requirement was critical when conceptualising the design because we needed to use simple, scalable, and affordable solutions to provide a massive construction volume.

Nüwa accommodates 250,000 people and provides 55 million square meters of total built-up area and 188 million cubic meters of breathable air. The modularity, urban strategy, and configuration inside a cliff are the results of such self-imposed constrain.

Tom Ravenscroft: What do you think the main barriers to building on Mars are?

Alfredo Munoz: The tunnelling systems, which are one of the most critical technologies required in Nüwa, are already available on Earth. Steel would be the primary material for civil work, as it can be obtained through processing water and CO2, which are available on Mars. While the team of scientists feels comfortable that such processing is possible, the technology has to be developed and tested on Earth.

However, considering the relevance of mining and excavation in Nüwa, a geotechnical analysis should be performed on the ground by astronauts to thoroughly verify and analyse if the conditions are adequate for extensive excavations on Tempe Mensa or new locations have to be scouted.

As a result, until we cannot send a limited number of humans to Mars, we will not have the intel needed to develop the detailed construction plans. While a lot of work can be performed with prototypes and analogues on Earth, astronauts should validate everything on the ground.

From the life-support point of view, the processing of oxygen is the most challenging technology that has to be developed. Although the vegetation in Nüwa provides oxygen, a large percentage needs to be "manufactured".

We still do not have the technology to create such a breathable air volume, which is a critical path for Nüwa's feasibility. On the other hand, the solutions regarding food, such as hydroponic systems for the crop, cellular meat, or microalgae-based food, are almost currently ready.

From the energy aspect, the solar generation systems of Nüwa are based on photovoltaics and solar concentrators, which are also available nowadays on Earth. The most significant problem we have on Mars is that solar power does not work during common sand storms. During those times, alternative energy sources need to be provided. While Nüwa is considering a small nuclear plant, further technology should be developed as an ideal alternative.

Even if Nüwa could be technically possible during the following decades, we still need to transport such an amount of people. Sending so many people is a massive challenge, as we only have a window of opportunity every two years due to the distances and orbits of Earth and Mars. Elon Musk and Space X might help during this in the next decade, but a colossal technology improvement on space shuttles needs to happen for Nüwa to be open its doors.

Finally, the resources and the will have to be in place for Nüwa to be a reality. The Panama Canal required decades of work and massive sources. Similarly, a city on Mars will require a long-term vision and commitment.

Tom Ravenscroft: When do you expect a city of this scale could be constructed on Mars?

Alfredo Munoz: Based on the summary of barriers that I explained before and considering preliminary technical analysis with the scientists we estimate that by 2054 we could be able to start building a settlement like Nüwa.

However, this date is tentative as there are many critical paths associated with a city on Mars. If the right resources are in place and some of the required technologies on Earth support the speedy implementation, Nüwa could be finished by 2100.

Images are by ABIBOO / SONet

The post ABIBOO envisions cliff-face city as "future capital of Mars" appeared first on Dezeen.

from Dezeen https://ift.tt/3cTXND4

No comments:

Post a Comment